Leonard Cohen's 'Hallelujah' as Cultural Artifact

The Minor Fall, The Major Lift

Three amazing things. First, in my 30-plus years of concert-going I’ve seen a helluva lot of concerts by performers known for their live shows. I’ve seen U2, Tom Petty, Elvis Costello, The Who, The Kinks, The Stones, Springsteen… at this point, the only act that could get me into an arena would be a Beatles show with the original lineup and Jesus on keys. The best show I’ve ever been to, however, was Leonard Cohen’s gig at the Fox a couple of years ago. In terms of musicality, showmanship, beauty and sheer endurance (three hours without flagging), the then-75-year-old Cohen and his band put on a show that was nothing less than transcendent. Cohen has just announced new tour dates, and if he comes back this way, go. Find the money and just go.

Three amazing things. First, in my 30-plus years of concert-going I’ve seen a helluva lot of concerts by performers known for their live shows. I’ve seen U2, Tom Petty, Elvis Costello, The Who, The Kinks, The Stones, Springsteen… at this point, the only act that could get me into an arena would be a Beatles show with the original lineup and Jesus on keys. The best show I’ve ever been to, however, was Leonard Cohen’s gig at the Fox a couple of years ago. In terms of musicality, showmanship, beauty and sheer endurance (three hours without flagging), the then-75-year-old Cohen and his band put on a show that was nothing less than transcendent. Cohen has just announced new tour dates, and if he comes back this way, go. Find the money and just go.

The second amazing thing is about Cohen’s near-ubiquitous anthem to love, sex and faith, “Hallelujah”: It will shut people up at karaoke. At Dr. Fred’s Thursday night gig at Go Bar my wife will occasionally get up and do “Hallelujah” and the usual incessant and often damnably rude audience chatter will cease, as if God pushed the “mute” button on His Universal Remote, the moment the opening bars kick in. And then people will sing along, often in harmony, softly and reverently at first and then building until the entire bar—hipsters and tourists, straights and freaks—is a veritable “Hallelujah” chorus.

The third amazing thing is that “Hallelujah” has become such a pervasive song in the musical firmament—countless covers, performances on glory-notes competition TV shows the world over, and for 20 years the go-to song to accompany any filmic montage on the theme of “melancholy”—and yet it originally tracked on an album that was shelved by Cohen’s label, Various Positions, recorded in 1984. The song has been used so often (incredibly, I’ve seen it in a book of wedding songs) that even Cohen, who collects the royalty checks on it, has mused publicly that people should perhaps stop performing it, and yet its success was purely by accident and sheer dumb luck.

It is a fact that, despite Cohen’s undeniable power as a songwriter, the downbeat sensibility of his songs and his limited range as a singer kept him at a distance from the mainstream success enjoyed by peers like Bob Dylan. For a long time, Cohen was a cult figure for musical pilgrims willing to forge into the hinterlands. It’s also a fact that while certain of Cohen’s songs—“Suzanne,” “So Long, Marianne,” “Who by Fire?”—can only be done justice by Cohen’s trademark smoker’s gravel, others have been covered by other artists and vastly improved. “Hallelujah” is one of the latter sort and is far better known as a track on the late wunderkind Jeff Buckley’s sole album Grace than as a Cohen composition.

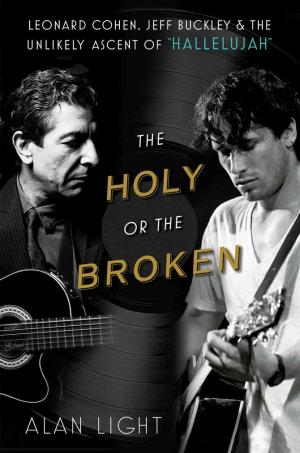

Alan Light, former editor-in-chief of Spin and Vibe, tracks the history of the song in his new book The Holy or the Broken: Leonard Cohen, Jeff Buckley and the Unlikely Ascent of “Hallelujah” (Simon & Schuster, 2012) and the result is fascinating. Beginning with a microscopic dissection of the song’s elements, its juxtapositions between Old Testament imagery and modern sexuality, its shrewd dip into music theory (the lines “the fourth, the fifth, the minor fall, the major lift” are placed precisely on a fourth, a fifth, a minor fall and a major lift, respectively), its meditations on searching for the sacred in the profane and failing and its playfulness, a point often lost in consideration of the piece, Light then follows the song like one follows a paper boat from gutter stream all the way to the vast ocean. He asks countless artists to give their take on the song and receives a plethora of answers.

And then there’s the parallel story of how Jeff Buckley, long-lost son of the folk artist Tim Buckley, heard John Cale’s cover of the song and developed an obsession with it, incorporating it nightly into his apprenticeship in Village clubs and building his reputation on his quietly powerful delivery and making the song his own. By the time it was included on the Grace album, “Hallelujah” was mistaken by many for a Buckley composition, while for others it became an introduction to Cohen’s music and the start of a fandom that has since grown far beyond anything Cohen had achieved on his own.

Light goes on to note the song’s appearance in the movie Shrek (Cale in the movie, Rufus Wainwright on the soundtrack album), its use as an anthem behind widely disseminated montage footage of the events of 9/11, and then its ubiquity in TV shows like "Scrubs," "The West Wing" and "House," among many others, and its now-regular place as a reliable show-stopping number for international artists and their would-bes on Simon Cowell talent shows. Whatever Cohen’s original intent for the song may have been, he created a malleable masterpiece, a Rosetta Stone of a song that fits so many different interpretations and evokes so many different reactions that it is no longer his but now belongs to everyone.

The notion of building an entire book around a single piece of music is hardly new—Greil Marcus made a cottage industry out of it—but Light’s book is a poignant reminder of how a song, the right song, can evolve from a piece of disposable pop in a sea of musical flotsam into a genuine cultural artifact. Light demonstrates how a single piece of art can pass into the world’s possession. He shows us why this song in particular shuts people up at karaoke, because it shuts people up everywhere, in the best possible way.

comments