City Pages

A Firm Foundation?

Trust The Trustees

University of Georgia President Michael Adams traveled to the land of schnitzel and lederhosen last week to visit a study-abroad site, a favorite summer activity for the college chief. If he was wise, he went on his own dime. While Adams was sampling the delights of the old world in Innsbruck, Austria, members of the influential UGA Foundation launched a review of the president's spending and decision-making, asking for a detailed look at Adams' use of private foundation funds. Some have been miffed, we're told, about the chief's decision to charter a plane to the 2001 presidential inauguration, his controversial $255,250 severance payment to fired UGA football coach Jim Donnan, and other costly decisions.

Any Bulldog diehard can see that the timing of the board's fishing expedition is not random. But concern about Adams' spending and decision-making is nothing new among some board members.

A cue toward the group's mixed attitude to the UGA leader can be taken from a move it approved more than one year ago, long before Adams' tense relationship with Athletic Director Vince Dooley broke out into a state-wide feud. The board restructured its spending process so that every expenditure by Adams from "presidential accounts" must be approved line by line by the board's chairman and finance committee chairman – a new accounting practice for the board that hardly seems a ringing endorsement of Adams' fiscal restraint. (The board, composed mostly of well-heeled businesspeople, maintains endowments for academic programs and administers funds for Adams' travel, dining and the like.) Asked if the group has been reining in a free-spending president, Board Chairman Jack Rooker told Flagpole: "This is a procedure the finance committee said they wanted to follow."

Indeed. The finance committee chair at the time was attorney Wyck Knox, the same UGA trustee who together with trustee Rachel Conway called last week's special meeting of trustees to discuss "recent events." (Read: the flap over Adams' decision not to extend Dooley's contract a requested four years.) For his part, Rooker, a six-year veteran of the foundation board, has been publicly supportive of the president, as has been the state Board of Regents, which is the body empowered to hire and fire state college presidents. "We've got big things to do at the University of Georgia," Rooker told Flagpole. "We're going to continue to upgrade everything."

Historically, one of the things the foundation board upgrades best is the president's pay, when it's in that sort of mood. Adams got a $79,000 boost to his deferred compensation plan from the private UGA Foundation board this year, a year when most state employees are doing without raises and fearing job cuts. It's also come to the attention of Flagpole that Hank Huckaby, Adam's senior vice president for finance and administration, accepted a bonus from the foundation in this year of belt-tightening. The hard-working Huckaby was awarded a $30,000 payout in private funds for serving as Gov. Sonny Perdue's temporary chief financial officer. Huckaby oversaw the mixing of a bitter cocktail of tuition hikes, rising health care costs, vacant teaching jobs, and higher taxes that promises to make this budget crunch memorable for most ordinary Georgians and ordinary faculty and staff.

Rumor had it that Adams had pushed for a bigger chunk of change for Huckaby, but Rooker denies the president's role in the perk. "Dr. Adams didn't have anything to do with it. It came up in a normal sort of sequence." After a year of athletic cheating scandals and shrinking budgets, one has to ask the question: Who says Adams shouldn't have a say in who runs the athletic department in the coming years? After all, even in these tough financial and political times, Adams has elevated a key administrative skill to championship levels: raising the executive standard of living without lifting a finger.

Joan Stroer

Joan Stroer is a local freelance writer.

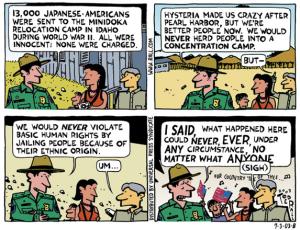

WMD: Cracking Bush's Facade

Bush lied about the weapons of mass destruction. He lied to us, the United Nations, and the soldiers he sent to die in Iraq. Bush's apologists defend his attempts to sell this obscene war as mere spin, but claiming certain knowledge of something that doesn't exist is hardly a question of emphasis. It's time to stop wondering where the WMDs are. Even if nukes and gases and anthrax turn up in prodigious quantities, it won't matter. Proof of Bush's perfidy, unlike his accusations that Saddam had something to do with 9/11, is irrefutable.

Before he ordered U.S. forces to kill and maim tens of thousands of innocent Iraqi soldiers and civilians, Bush and Co. repeatedly maintained that they had absolute proof that Saddam Hussein still possessed WMDs. "There is no doubt that Saddam Hussein now has weapons of mass destruction," Dick Cheney said in August. In January, Ari Fleisher said: "We know for a fact that there are weapons there." WMDs; not a "WMD program" as they now refer to it. WMDs - not just indications of possible, or probable, WMDs.

Before he ordered U.S. forces to kill and maim tens of thousands of innocent Iraqi soldiers and civilians, Bush and Co. repeatedly maintained that they had absolute proof that Saddam Hussein still possessed WMDs. "There is no doubt that Saddam Hussein now has weapons of mass destruction," Dick Cheney said in August. In January, Ari Fleisher said: "We know for a fact that there are weapons there." WMDs; not a "WMD program" as they now refer to it. WMDs - not just indications of possible, or probable, WMDs.

Absolute proof.

During the first days of the war, Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld stared into television cameras, looked right at his employers (that's you and me), and said that he knew exactly where they were. "We know where they are," Rumsfeld said. "They are in the area around Tikrit and Baghdad."

Uh-huh. So where are they?

"Absolute" proof is a high standard - heck, it's a nearly impossible benchmark. The last time I checked, my cat was in my kitchen, licking the milk at the bottom of my cereal bowl. As intel goes, mine is triple-A-rated - I witnessed it this morning, and I've spent the better part of a decade observing that animal. But if you were to demand absolute proof of kitty's current location, I couldn't give it to you. I'd bet that he's sleeping on my bed. But he could be in the litter box, on the windowsill, or sneaking out an open window. Truth is, I don't know where he is. To say otherwise, to present even a well-founded hypothesis as fact, would be a lie.

Bush had conjecture, wishful thinking and stale intelligence going for him. He needed absolute proof, and the absence thereof is leading to talk of impeachment. Before the invasion of Iraq, Rumsfeld argues, "Virtually everyone agreed they did [have WMDs] - in Congress, in successive Democratic and Republican administrations, in the intelligence communities here in the United States, and also in foreign countries and at the U.N., even among those countries that did not favor military action in Iraq." Untrue.

Most people, me included, guessed that Iraq probably had WMDs. (Those of us who opposed the war figured that Iraq's post-Gulf War partitioning, trade sanctions and maximum 400-mile missile range limited its potential threat to the United States.) The last time we knew for sure that Iraq had WMDs was 1998. The American public, nervous about Bush's radical new policy of preemptive warfare, would not have supported a war based on maybes. In September 2002 only 18 percent of Americans thought attacking Saddam would make America safer. They demanded proof of an imminent threat before they would back military action.

The Bush Administration didn't have proof, so they spent last fall making it up. As Robin Cook, who resigned from Tony Blair's cabinet over the war, told the British Parliament: "Instead of using intelligence as evidence on which to base a decision about policy, we used intelligence as the basis to justify a policy on which we had already decided."

By January 2003, 81 percent of respondents to an ABC News poll said they believed that Iraq "posed a threat to the United States."

Previous administrations, reliant on the CIA for reliable information, have traditionally respected a "Chinese wall" between Langley and the White House. As Republicans blame the CIA for the missing WMDs, leaks from within the CIA increasingly indicate that Dick Cheney and others sought to politicize its reports on Iraq, cherry-picking factoids that backed its war cry and dismissing those that didn't. This dubious practice culminated with Colin Powell's over-the-top performance before the U.N., where he misrepresented documents he knew to be forged - which he privately derided as "bullshit"! - as hard fact.

The Administration's defenders, whose selective morality makes Bill Clinton look like a saint, argue that the WMDs don't matter, that Saddam's mass graves vindicate the war liars. But no one ever denied that Hussein was evil. The American people knew that Saddam was a butcher during the '80s when we backed him, and during the '90s when we contained him. They weren't willing to go to war over regime change in the '00s, which is why the Administration invented a fictional threat. Now that we know that presidents lie about the need for war, how will future presidents rally us against genuine dangers?

Lying to the American people is impeachable. Waging war without cause is subject to prosecution at the International War Crimes Tribunal in The Hague. But insiders have to talk before the media can aggressively pursue the WMD story, prosecutors can be appointed and top evildoers brought to justice.

Now Slaughtergate has its own Alexander Butterfield. Christian Westermann, a respected State Department intelligence analyst talking to Congress, has testified that Undersecretary of State John Bolton, a Bush political appointee, pressured him to change a report on Cuba so that it would back Bush claims that Cuba was developing biological weapons. Westermann says that when he refused, Bolton tried to have him transferred.

Westermann's testimony doesn't relate to Iraq, but it puts the lie to Bushoid assertions that they never messed with the CIA. A reliable source informs me that there's a "jihad" underway between Administration political operatives and the career intelligence community. "Guys are pissed off that they're being asked to take the fall for the White House. Look for more leaks in the future," this official says.

Meanwhile, Gen. Richard Meyers, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, has been reduced to parsing the meaning of intelligence: "Intelligence doesn't necessarily mean something is true," he says.

Now he tells us.

Ted Rall

Ted Rall is a syndicated columnist and cartoonist.

Centralization Of Local News

The television anchor for WSMH - the Fox TV affiliate in Flint, Michigan - recently gave listeners the local weather forecast, saying it's going to be a high "of 57 for us here in Flint."

Us? This anchor was actually hundreds of miles away in the Baltimore area, working out of the centralized television studio of the Sinclair Broadcast Group, which owns 62 television stations in cities like Flint, Tampa, Pittsburgh, Raleigh, Rochester, Birmingham and Oklahoma City.

Weather is not the only news item removed from local control by the Sinclair chain. For example, Flint's local news team gets seven minutes on the 10 o'clock news, then the station switches to yet another anchor who's also in faraway Baltimore, but pretending to be in Flint as part of the "local" broadcast. Sinclair refers to this deception as "central casting."

Welcome to your "news" future under the magic of the recent un-regulation of our public airwaves by the FCC, allowing more profiteering conglomerates to seize control of our independent, local sources of news and information. Under the monopoly-friendly rules rammed through by industry lobbyists and Bush appointees to the FCC, we're headed for an orgy of media mergers, giving even greater control to a handful of giants over what we see, hear, and read.

As one of the industry's leading investment analysts so starkly puts it: "The biggest implications of the rule changes is that everyone has to decide whether they want to be a buyer or a seller in the next five years. The map will change within that time period. The big are going to get bigger." Swell. As they get bigger, our news gets more consolidated and centralized, reduced to remote, cookie-cutter, corporate homogeneity ñ and our democracy shrinks.

This is Jim Hightower saying... To fight this monopolized mono-casting and theft of our public airwaves, call the Media Access Project: (202) 232-4300.

Jim Hightower

Jim Hightower is a political columnist, radio commentator and former Texas agriculture commissioner.

One Woman's Memories Of Forgotten Afghanistan

"The struggle of man against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting." - Milan Kundera, The Book of Laughter and Forgetting

There was a dispiriting piece in The New York Times Magazine of June 1 on the resurgence of feudal chiefs in Afghanistan. It seemed oddly out of place. (Huh? Afghanistan? What does that have to do with anything?) The zigzag tour we've taken of Central Asia since 9/11 and America's notoriously poor memory have left Afghanistan, sadly, not surprisingly, stage left. Iraq was the new Afghanistan. Iran is the new Iraq. It makes Christina Lamb's Sewing Circles of Herat (Harper Collins, $24.95, 368 pp.) her personal and thorough account of two wars in Afghanistan - that much more significant.

Lamb is an award-winning foreign correspondent who covered the mujaheddin-Soviet war in Afghanistan in the late 1980s and then returned after 9/11. She writes about two different wars with similar horrific results. Both of which are, for the most part, forgotten. Lamb published her book on the heels of War in Afghanistan II. It seemed a perfect coda - portrait of a troubled country before we fixed it. The upshot is that it's about as fixable as shattered glass. What is left of Afghanistan after centuries of brutal wars, oppression and depraved destruction is essentially rubble. Which might be why it's slipped out of the news - there's no "there" there.

Lamb arrived in Afghanistan an idealistic adventurer "stumbling out of a battered mini-bus in the Old City of the frontier town of Peshawar, dizzy with Kipling and diesel fumes." She had romantic notions of faraway adventures and despite the horrors she had seen, the romantic notions persist on her return to the country years later. In the midst of mass destruction, death and ruin, Lamb is quick to point out the bird singing, the lone flower pushing defiantly through the dirt, the smell of a pine tree. She captures the essence of culture, tradition and pride of a people that is impossible to see in news accounts.

The title of the book refers to one of the only social gatherings allowed in Afghanistan under the Taliban regime. Using sewing circles as a cover, women carried baskets of needles, thread and cloth to houses where they gathered to write, read poetry, teach and learn. Children playing in the street were instructed to signal if Taliban approached so they could hide their books and pick up sewing needles. The art, beauty and intellectual fulfillment these women craved enough to risk their lives for was very strictly forbidden. Lamb uses their story to weave together the country's complicated history. She juxtaposes images of beauty and horror throughout the book - a metaphor for her own writing. Lamb believes passionately that stories, no matter how horrible, need to be told, and beauty is never completely lost.

Some of her accounts are literally jaw-dropping. Traveling the country with the mujahedeen in the '80s she spent two days huddled in a trench waiting out Russian tanks parked at close range ready to shoot any sign of life. The group of men in the trench included current Afghanistan President Hamid Karzai, with whom she forged a close friendship. They lived on dirty puddle water and mud crabs until the tanks inexplicably drove away.

One of the eeriest sections of the book, "Mullahs on Motorbikes," is an account of her friendships with the men who later became the Taliban. At the time they were fighting the Soviet Union - idealistic youths who loved their country yet a few years later systematically destroyed it. In those earlier days she writes, "I found them brave men with noble faces who exuded masculinity yet loved to walk hand-in-hand with each other and pick flowers."

Later she describes the atrocities committed by the regime they formed: public executions, torture and unimaginable destruction. It's an unsettling comparison - one visit she's laughing with the mullahs, the next she's recording horrific carnage at their hands. When the oppressive Taliban regime is finally toppled in Afghanistan, all that remains of the country's jeweled past are stories. The Taliban's focused efforts to destroy art, culture and history recall more recent events in Iraq - the annihilation of a country's soul.

Sewing Circles of Herat ends on a just barely positive note. Lamb tracks down a young girl whose letters are sprinkled throughout the book. She wrote to Lamb secretly during the Taliban, describing life under their rule candidly enough to get her killed, if she had been caught. Lamb developed a strong emotional attachment to this girl through her intimate conversations in letters and when they finally meet, exchanging hugs and gifts, things seem to be looking up. But it's a sitcom conclusion - one that American readers look for. We're accustomed to neat, happy endings, whether they are neat and happy or not. Certainly Lamb didn't leave the country with excess optimism. Nobody could have.

Though heartbreaking, Lamb's book is a beautiful gift to Afghanistan and essential to understanding a people beyond news clips. She is also the author of The Africa House: The True Story of an Englishman and His African Dream and Waiting for Allah: Pakistan's Struggle for Democracy.

Teresa DiFalco

Teresa DiFalco is associate books editor of PopMatters.

Confessions of a Meigs Street Crazy

I first came to Athens with the Lighthouse Family commune in the fall of 1969. Near the end of winter, 1970, I came to live here full-time. The commune had moved on to the Atlanta area with a house in Midtown and a farm out in Rockdale County. A few of us had taken quite a liking to Athens and decided to stay here. I shared an apartment with a good friend and co-conspirator from the commune, Richard Eldredge.

About mid-week in early August I was going to Atlanta for a few days to visit at the commune for a couple of days. Somehow just on a whim I dared Dick and his high school friend Ellie, who had come to visit, to have a lemonade stand out in front of the Station House, which is what I nicknamed the two-story house where we lived. It had to be from 10 p.m. till 4 a.m. Another wrinkle was they could only serve real lemonade with nothing other than natural ingredients in it. The final joke was that they were both honor bound to not reveal whether there was anything unnatural in it. Think of this as a variation of Ken Kesey's electric Kool Aid acid test, but a placebo test instead. So I thought nothing more of my dare to them and off I went to the big city.

I caught a ride back from Atlanta with Clarksville Andy and his good friend Dickie. We rode back up here in Dickie's Mustang, one of those of the vintage era, and the ride was pretty quick. When we turned onto Meigs from Milledge we had to park the car almost a block up the street. We could see this eerie purple glow, and we could hear the sounds of voices out in front of the Station House. Well, Dick and Ellie had taken the dare and run long and hard with it. They had made two signs with dayglow paint: one was spelled Lemonade and the second was spelled Lemonade with initials JA on the bottom of the sign ("junior achievement," a private joke of Ellie's). They had wrestled a dresser from my room and both of my black lights were in use giving the glow. There were a dozen people there, and they were indeed enjoying themselves. They had held true to the rules: not a mention of whether there was anything funny in it or not. This would mark the first of a dozen Meigs Street lemonade stands that were held there over the next three years.

Each one was a little larger than the one previous to it, and it was a means for people to connect to one another. Cool people would see it and stop; people who tuned out just kept on driving by not the wiser for it, sadly. The lemonade stands gave us hippies a way and place to gather. Drugs and alcohol were not a part of its inner workings. If people came who were on drugs or drunk, this was not of our doing. The police never were summoned once in all of the 12 gatherings. The first stand was in August, 1970 and the last was held on an early Friday evening in August, 1973. There were close to 300 people for the last Meigs Street Lemonade Stand.

E. G. (Rick) Baker

Rick Baker is a local writer and computer consultant.

Help Fix Up Cook's Trail

Spend a day on the Greenway learning about Cook's Trail while helping to maintain it: Saturday, July 12 from 10 a.m. to 1:30 p.m. For information, call Sadie D. Wilks, volunteer coordinator, at (706) 613-3615 ext. 227.

comments