TIME After TIME: How Magazine Coverage of the South Changed From 1964–2018

Cobbloviate

TIME magazine’s Aug. 6-13, 2018 issue was dedicated to the South and featured Georgia Democratic gubernatorial hopeful Stacey Abrams on the cover. In conjunction with this issue, the nice folks at time.com asked the Ol’ Bloviator to look at TIME’s take on the South way back in the critical year of 1964. What follows is a close approximation of that piece.

It was a regular occurrence during the 1950s and ‘60s: New York-based publications like TIME, Newsweek and Harper’s regularly devoted special issues or special sections of regular issues to the South. All of them focused in one way or another on assessing the region’s progress in surmounting the barriers of racism, poverty and educational backwardness that continued to separate it from the rest of the country—meaning, effectively, the Northern states, which had long served as the embodiment of American ideals of virtue, enlightenment and prosperity.

This was no random practice. After all, the nation was in the throes of a civil rights movement, which at that point, was concentrated on toppling the entrenched Jim Crow system that still set the South apart. By the middle of the 1960s, however, forces were already stirring that would soon shatter the perception of a Southern monopoly on racism and cast serious doubt on the presumption of superior Northern virtue.

Sensing that the Civil Rights Act of 1964, passed and speedily signed into law on July 2, marked a truly “historic turning point in the relations between the races in the U.S.,” the editors of TIME devoted a portion of the July 17, 1964, edition to assessing Southern reaction to the law during the first week that it was in effect. Though it had been 10 years since the Supreme Court declared de jure segregation in the public schools unconstitutional, fewer than one in 10 black pupils in the states where dual school systems had supposedly been outlawed were actually attending racially integrated schools. Now, with its sweeping prohibition of racial discrimination in public accommodations, such as restaurants and hotels, the Civil Rights Act promised more integration overnight than the court’s decree had accomplished in a decade.

Despite warnings that such peremptory federal action might trigger a “race war” in the South, to the clear relief of TIME’s editors one week in, this did not seem to be in the offing. Across the South, blacks and whites were seen eating and lodging together without incident in citadels of segregation like Birmingham, AL, Memphis, TN and Jackson, MS; and in Greenville, SC, a young black man sat in the same hotel dining room as Sen. J. Strom Thurmond, the chief filibusterer against the Civil Rights Act.

It wasn’t all pretty, to be sure. In Bessemer, AL, whites beat six black lunch-counter customers with baseball bats, and two men were wounded during a “wade in” at a lake in Texarkana, TX. More ominously, in rural North Georgia, near Athens, a shotgun blast from a passing car had killed black educator and Army Reserve officer Lemuel Penn. Still, in all, TIME’s editors thought that “the South’s initial compliance with the new Civil Rights law was, by any standard, encouraging.”

This guarded optimism also surfaced in a companion piece in this issue, which hailed segregationist Louisiana Sen. Allen Ellender’s warning that any further Southern opposition to the Civil Rights Act must respect “the orderly process established by law” as “a statement of stunning reasonableness,” as reason to hope that future resistance might at least be pursued by legal rather than extralegal means.

The generally peaceful white acquiescence to the Civil Rights Act suggested that even if white Southerners’ feelings about their black neighbors were impervious to legislation, their overt behavior was not. The readiness of black Southerners to step forward to test the actual viability of the new statute was also heartening, though hardly more so than their courage and resolve in responding to the Freedom Summer voter registration effort then underway.

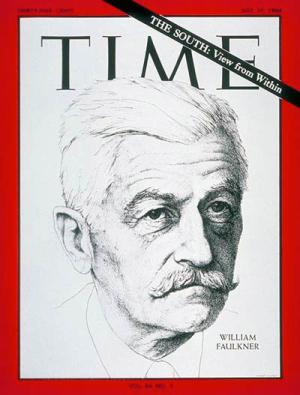

The cover of this issue of TIME bore a sketch of William Faulkner, and its cover story delved into Faulkner's writings for "a deeper analysis of the traditions, emotions and psychological factors" that were at once the root of the race problem in the South and the key to its solution. When it came to improving Southern race relations, Faulkner would seem at first glance an unlikely source of encouragement. In fact, he had been among those who warned of potential bloodshed if the federal government moved too abruptly to dismantle segregation, and his dark and savage portrayals of white racial hatred in novels like Light in August hardly inspired optimism. Yet his fiction also offered characters like Isaac McCaslin in Go Down Moses, who was dogged by guilt and struggled desperately to find the personal courage to reject the white South's racist rituals and dogma. In this respect, Faulkner also invested great hope in a younger generation of white Southerners like Chick Mallison in Intruder in the Dust, who had developed a healthy skepticism of such unhealthy practices early on. Faulkner saw the South's ultimate racial salvation coming not from legal coercion, but from changes in the mindset of the region's whites, but while surprised, he might also have understood that their general accommodation to the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was at least reason to hope that the change of heart that he had worked so hard to effect might at last be underway.

Still optimistic about the region’s prospects as they might have been at that point, TIME’s editors and writers could hardly have imagined that within scarcely a decade, the South would not simply be “accepted into the fraternity of states,” as one writer put it, but wielding substantial influence over national affairs. This remarkable upgrade in regional standing reflected not only continued progress in the South, but striking changes in the confidence and relative moral authority of those Americans who had long judged its progress from distant perches north of the Mason-Dixon line.

Though they could hardly be recognized as such in mid-1964, some of the forces behind this jarring shakeup were beginning to stir even as TIME’s take on the South went to press. The “white backlash” against the civil rights movement, which would soon envelop the entire country, was foretold in the presidential campaign of Barry Goldwater, a staunch opponent of the Civil Rights Act, who accepted the Republican nomination on July 16, the day before the official publication date of that issue. Goldwater’s blatant courtship of lifelong white Democrats outraged by their party’s aggressive embrace of the Civil Rights agenda won him five Deep South states that November and set the stage for Richard Nixon’s more skillfully implemented “Southern strategy,” which also played well nationally four years later. The white backlash would expand and intensify exponentially in the face of surging black violence in the nation’s inner cities that was just beginning to manifest itself in the Harlem Riot, which also erupted just as the TIME issue appeared and some three weeks before a similar conflagration in Philadelphia.

Despite TIME’s focus on the South, these riots and the dozens to follow, not to mention the mounting white outcry against forced integration in places like Chicago and old abolitionist Boston, gave ample proof that racial intolerance was every bit as real and just as ugly up North as down South.

Finally, three weeks after the TIME issue appeared, Congress approved the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution granting President Lyndon Johnson virtual carte blanche to escalate U.S. military involvement in Vietnam. Though hardly foreseeable at that point, this was a critical step toward creating a new object of national outrage that sapped the civil rights campaign of much of its sense of moral urgency. It also quickened the nation’s march into a spirit-devouring swamp of futility and failure from which the legend of American invincibility would not emerge intact. Then, with the U.S. still struggling to extricate itself from this quagmire, the Watergate scandal blew a gaping hole in the almost foundational myth of national innocence and virtue. Even further indication of a nation turned downside-up came in almost daily reports of once dynamic Northern cities hemorrhaging jobs, capital and people to the more salubrious business and living climates of a suddenly vibrant Southern corridor.

As these developments compounded, historian C. Vann Woodward noted that “the old grounds for Northern moral superiority gave way” and “self-righteousness withered along the Massachusetts-Michigan axis.”

Interestingly enough, Woodward’s commentary appeared in the Sept. 27, 1976, issue of TIME, which was largely devoted to a South that no longer seemed an iffy destination, but a beckoning land of “spectacular beauty,” where yesterday’s night-riding rednecks were today’s laid-back, fun-loving “good ol’ boys” like Billy Carter. Meanwhile, Billy’s more buttoned-down older brother, Jimmy, whose regional heritage helped to inoculate him against the crippling effects of failure or guilt, stood ready to lead the nation out of its post- apocalyptic funk. In short, as an optimistic Saturday Review writer had put it a few weeks earlier, here was a South no longer walled off from the rest of the nation, but one whose racial progress, capable leaders, and dynamic economy seemed to offer “a foretaste of the New America.”

That this suggestion proved prophetic, albeit largely in ways that ran counter to the liberal writer’s hopes, should not have been surprising. Nor should we resist seeking a glimpse of the nation’s future in a South still very much in transition today. If the developments between TIME’s South-conscious issues of 1964 and 1976 revealed nothing else, it was that, even at its worst, the region had always been not only a part of America, but in a very real sense, a window into its soul.

comments