Ghost Fry

The Strolling Player's Tragedy: Sol Smith in Georgia, 1832-1837 - Part Four

Sol Smith, actor, playwright, theatrical manager and, most recently, lawyer, returned to Milledgeville, Ga., at the beginning of February 1834 to assist in the prosecution of William Flournoy, a wealthy planter who had killed Smith's brother Lemuel in a brothel more than a year before. At that time it was fairly common for interested parties in criminal prosecutions to retain private counsel to assist the state in the prosecution. The defendant, Flournoy, had hired any lawyer of any reputation in Baldwin County, so Smith had been obliged to go to Macon for legal assistance.

The trial was set for Feb. 3 at 2 o'clock. The prosecution stressed the fact that Flournoy had shot Lem Smith in cold blood, mistaking, or pretending to mistake, him for someone who had insulted him in Eatonton. The defense dwelt heavily on Lem Smith's statement to a friend in the brothel that he was ready for him. The defense showed that Smith had a pistol at the time of the shooting and had fired it. The fact that it had no bullet and had gone off in his pocket did little to shake the self-defense argument that Flournoy's lawyers were constructing for him.

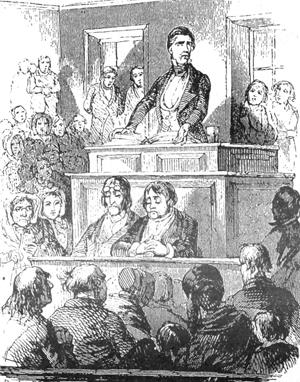

The trial went on past sundown and the lamps were lit. Near midnight Sol Smith rose to question Flournoy. According to Smith's account, he pointed to the accused, called him a cold-blooded killer, and prophesied that, whatever the verdict, he would be marked for life and damned to sleepless agony. The spectacle of a man confronting his brother's killer by flickering lamps at midnight in a silent, crowded courtroom was probably one that the jury carried with them for the rest of their lives. It did not, however, sway their judgement. Arguments continued till 5 a.m.; the jury was sent out and returned in 10 minutes, finding William Flournoy not guilty by reason of self-defense.

Bitter, Smith returned to Montgomery and went back on the road with his company. More than two years passed. In May 1836 Smith found himself in Columbus, Ga., just as war was breaking out between the Creek nation and the whites of lower Alabama and Georgia. Smith needed to get across lower Alabama and wanted to get the Chattahoochee ferry as soon as possible. He went to a livery stable to hire a coach and there he was approached by a gaunt figure who, though greatly changed, was still recognizable as William Flournoy.

In Smith's account Flournoy approached him and said he had been looking for him for two years. He said that, as Smith had predicted, he had been able to sleep only by drinking himself into unconsciousness and that now he wanted only to die. He asked Smith to shoot him there on the street. Horrified, Smith refused. He told Flournoy that it was not his place to punish him, to which Flournoy replied, "It is not punishment... but it is vengeance I wish you to take..." Smith told him to seek forgiveness but Flournoy said that he could not be forgiven until vengeance was taken for his crime. Smith again refused, and turned away. He claimed that the last words he heard Flournoy say were "I will die tonight."

Smith, the master of stage business, may not have been above improving Flournoy's lines, but he could hardly have confected a more lurid melodrama than the one that soon transpired. Flournoy set out alone that night for his plantation below Columbus. The next day his bullet-riddled body was discovered, the first victim of the Third Creek War. A year and half later Flournoy's watch was found on the body of a dead Seminole warrior in Florida. The Creeks had rung down the curtain on Sol Smith's career in Georgia, just as they had opened it five years before in the new Columbus theater.

Smith continued in the theater for decades, finally retiring to St. Louis, where he entered politics and played a role in keeping Missouri in the Union during the Civil War. He could never bring himself. to return to Milledgeville to see his brother's grave. He died in 1869. William Flournoy's Eatonton relatives inherited his plantation near Columbus and went on to become one of the most prominent families of that city.

©1994 John Ryan Seawright

comments