Ghost Fry

The Looking Glass: Orth Stein — Poet, Editor, Artist, Killer - Part Six

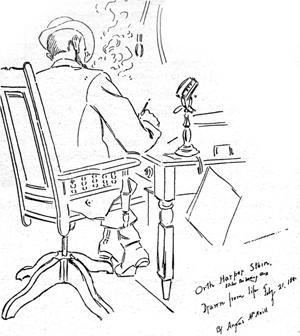

Drawing of Orth Harper Stein the editor of The Looking Glass

In September 1891 Orth Stein, traveling journalist, artist and acquitted murderer, found himself in the DeKalb County jail on a concealed weapons charge. The real reason for his arrest had been the rumor that he was a wanted criminal with a $10,000 price on his head. As it became clear that Stein's only unfinished legal business was a check forgery charge from Griffin, the reward seekers melted away, replaced by a stream of well-wishers who provided Stein with newspapers, flowers, cigars and pleasant conversation. The jailer's wife cooked his meals and the Atlanta YCMCA began working for his release.

While awaiting trial for murder in Missouri 10 years before, Stein had written and published at least one short story from his jail cell; he did the same in Decatur. Sunday, Sept. 20, the Atlanta Constitution published "A Case of Aphasia: A War Story by Orth Harper Stein."

"A Case of Aphasia" is a sugary bit of Old South romance, undoubtedly calculated wo win sympathy for its author: A Georgia plantation owner hides a fortune before going off to death in Confederate service; old Abe, the faithful slave, hides the treasure from Yankee deserters who knock him on the head; the impoverished family attends to the beloved old retainer after emancipation, listening to his garbled speech for years before the devoted little daughter realizes that he has been trying to communicate the hiding place of the gold.

The concealed weapons charge was soon dispensed with and Stein promised to repay the Griffin bank the amount of the forged check. He was released from jail and offered a job as an artist, engraver and writer for the Atlanta Journal. Stein's first bylined article for the Journal was a reminiscence of his days as a reporter in Leadville, Colo. Stein admitted that most of his reporting was ludicrous fiction, but claimed that it was so ridiculous that only the most naive reader would have mistaken it for anything else. Nonetheless, Stein attributes one of his famous hoaxes to a (probably imaginary) reporter named Schrader, and generally tries to extricate himself from his reputation as an irresponsible cynic.

Two weeks later the Journal printed Stein's "A Kodak Fiend at the 'Expo.'" Illustrated by the author, this was a series of humorous impressions of visitors and performers at the Atlanta Cotton States Exposition.

Stein worked at the Journal for a year. He apparently became well-known in Atlanta during this time and became closely acquainted with the city. In late 1892, he quit his job and went into business for himself. Undaunted by memories of the failure of the Comet, his first attempt at running his own newspaper, Orth Stein launched The Looking Glass, a superbly written and illustrated weekly newspaper, which was to enlighten, enrage and entertain Georgians for the next six years.

It is not clear where the money came from to start The Looking Glass. Stein was broke when he came to Atlanta and his journalist's wages would hardly have been sufficient for him to accumulate the necessary capital in a year, if ever. Stein had bankrupted his mother with his last newspaper venture, and such old friends as he might have still been in touch with would hardly have considered him the man to be trusted with several thousand dollars. As Stein and his paper grew in notoriety, the question of The Looking Glass' financing would arise again, but would never be resolved. Whoever made the investment probably made a good one: The Constitution and the Journal were very careful about treading on the toes of wealth and power in the state; they observed all the late-Victorian journalistic proprieties; they largely pretended that Atlanta housed neither vice nor eccentricity. The city's newspaper readers were past due for an infusion of lurid scandal. Orth Stein knew how to dish it up.

© 1994 John Ryan Seawright

comments