The Clarke County School District Shouldn't Ban Books

Comment

Editor's Note: The controversy over And the Earth Did Not Devour Him centers around the following passage, part of a worker's internal monologue after the truck carrying him breaks down.

"What a stupid woman! How could she be so dumb as to throw that diaper out the front of the truck. It came sliding along the canvas and good thing I had my glasses on or I would even have gotten the shit in my eyes! What a stupid woman! How could she do that? She should've known that crap would be blown towards all of us standing back here. Why the hell couldn't she just wait until we got to a gas station and dump the shit there?...

"This is the last fuckin' year I come out here. As soon as we get to the farm I'm getting the hell out. I'll go look for a job in Minneapolis. I'll be damned if I go back to Texas."

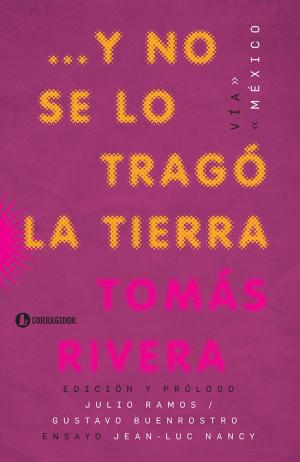

During a recent Clarke County Board of Education meeting, there was discussion about And the Earth Did Not Devour Him by Tomas Rivera, a work of literature that middle school students read, a book that won the first national award for Chicano literature in 1970 and, as Amazon.com puts it, “has become the standard text for Hispanic literature classes.” This is a book that Goodreads calls “a monument to a proud people’s unyielding search for a brighter future,” and is described by Ramon Salvidar of Stanford University as “a primary element of the new Mexican American literary history.”

Indeed, reading several pages of links found through an Internet search —including several study guides for teachers—not a single one hinted at anything other than that this is an outstanding work of literature that should be widely read.

Journalist Luis Torres was particularly eloquent, and I’d like to quote at some length from his posting as I think it is consistent with the life experience of many of the students in our middle schools:

"[This is] a little jolla of a book that was among the very first books we could actually classify as 'Chicano literature.' It’s the legendary gem by Tómas Rivera. Its actual title is—and it is written in lower case—…y no se lo tragó la tierra. The title of the book has been variously translated as And the Earth Did Not Part or …And the Earth Did Not Devour Him...

"I was a pretty voracious reader in high school. I read all the typical American writers that the English teachers recommended. I was enthralled by stories and ideas that were far removed from my own experiences growing up on L.A.’s eastside. I was captivated by different characters and moved by their motivations and desires and goals—and setbacks. But I was always looking for characters who looked like my family, talked like my family and, essentially, acknowledged that people like us existed. As a kid in the library the closest I got to that, it seemed, were some works by Steinbeck which included occasional glimpses into the lives of Mexican Americans or Mexicans.

"Then came …y no se lo tragó la tierra by Tómas Rivera.

"Again, this was 40 years ago. Here was a book that—what do you know?—was about us. It was about tios and tias and abuelitos. It was about the kind of backbreaking work that many of our families did at one time or another. It was about dreams and meditations that meant something to us. It was about characters and stories and ideas that were ours, as well as being universal. It was a revelation to read that little book so many years ago. And after reading it again very recently, it’s clear that it is a slice of American fiction that holds up to scrutiny and, beyond that, is likely to be established for generations to come as a beautifully written and thought-provoking work of art."

Few would disagree that challenging students with great literature is a major component of education. The professional educators in Clarke County and elsewhere have identified this and other books that not only are recognized as great literature, but also provide a connection for our students. This particular book provides connection, inspiration, and understanding across cultures.

As I understand it, two parents objected to the book because of concerns about some of the language, and Superintendent Philip Lanoue told them that their children, and any others whose parents objected, would be exempt from reading the book. That seems an eminently fair and appropriate response.

I understand that the parents filed an appeal, objecting that not only should their own child not read it, but that it should not be included in the reading list for other students. Their reasoning is that students are expected not to use such language, so reading a work of art in which a character uses such language is inconsistent with expectations for their own behavior.

That reasoning is specious at best. Our students read of assassinations, of terrorism, of deception, of myriad other activities in which we would not want them to engage. Is anyone suggesting that we remove books containing such unacceptable acts from students’ reading lists?

There is no work of literature that does not have opponents. If we want our children to grow into adults with critical thinking skills, they cannot be deprived of literature simply because someone, for some reason, objects to it. I personally did not like that school books my children read glorified war, in violation of my religious beliefs, but I did not ask that they not read them, let alone that others not read them.

The suggestion that our students are incapable of appropriate response to a renowned if challenging work of literature that is used in many middle schools reminds me of the still-too-common phenomenon of low expectations. CCSD’s numbers have shown significant improvement in recent years in large part because expectations are set high and support is provided to meet those expectations. Let us not move backward on that, and let us not return to the days when the Board of Education moved from its role in policy and governance into interfering with the professional judgment and day-to-day work of the superintendent and curricular staff.

One online commenter suggested that the District use John Steinbeck, but Grapes of Wrath has been banned in the past for—guess what?—its language. Other books that have been banned in schools include Beloved by Toni Morrison, The Call of the Wild by Jack London, The Catcher in the Rye by J. D. Salinger, For Whom the Bell Tolls by Ernest Hemingway, The Great Gatsby by Scott Fitzgerald, Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison, Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman, Moby Dick by Herman Melville, Native Son by Richard Wright, The Red Badge of Courage by Stephen Crane, The Scarlet Letter by Nathaniel Hawthorne, Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston, To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee, Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe, Where the Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendak and The Words of Cesar Chavez by Cesar Chevaz, among many others. All the titles listed in this paragraph are on the Library of Congress’s list of Books that Shaped America, and every one of them has been removed from the curriculum at one or more school districts.

Excluding books from Clarke County School District based on their language means that most of those in the previous paragraph would be removed, and also Shakespeare, the Bible and many others. If objections to content by any parents mean removal of a work for all students, you might as well stop teaching literature at all, or for that matter science, history, or any other subject matter. Someone objects to just about everything.

I do not understand why five Board of Education members have instructed the Superintendent to reconsider his decision. Presumably the reconsideration is not about the part of his decision that allows students to opt out of reading the book at the parents’ request, but is about the part of his decision to keep a renowned work of literature in the curriculum of students whose parents do not object.

Under its current makeup (and those of the last several years), I have almost never disagreed in any significant way with a decision of our Board of Education. However, I strongly disagree with this one.

While I’m disappointed that the board initially failed simply to uphold the professional staff’s position on this matter of curriculum, I am grateful that the board did not instruct the superintendent to remove the book from the reading list. I hope that he does not. As one who cares passionately about our schools, I fully expect the board will not further interfere if the superintendent allows the book to remain on the list.

Please, board members, do not remove great works of literature from our schools’ curriculum. Do not remove And the Earth Did Not Devour Him or any other work selected by our professional educators as part of the curriculum.

comments