Sexual Assaults at UGA—Often Fueled by Drinking—Go Unpunished

News Feature

Photo Credit: Porter McLeod

Greek Park, where UGA student Katherine Garcia says she was raped at a party in 2012.

Sunburned girls, sweaty and bleary-eyed from a day and long night of frat-hopping, streamed out of their last party at a University of Georgia fraternity house in Greek Park on Mar. 31, 2012. They were careful to step around 19-year old Katherine Garcia, who sat sobbing on the curb, legs and feet covered in blood.

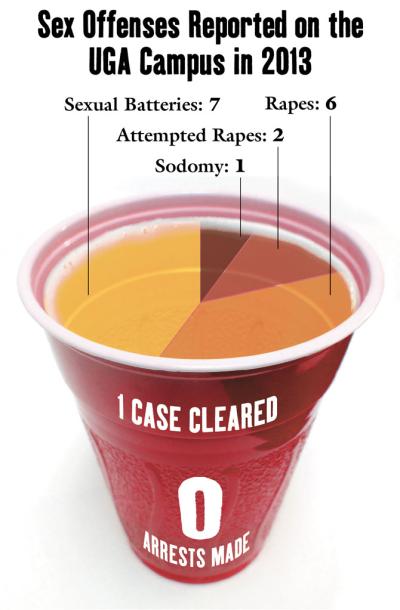

In 2013, 16 sexual offenses were reported on campus, according to the UGA Police Department’s crime statistics. None resulted in an arrest. The frequency of anonymous police reports, paired with the crime’s extremely low report rate, makes it difficult to track when, where and how many assaults actually occur in a given year. It’s even more difficult to prosecute aggressors, who are often friends or at least acquaintances of the victims.

What isn’t difficult is finding underage UGA students who have had nonconsensual sexual experiences at parties while under the influence of alcohol, which UGA Chief of Police Jimmy Williamson calls the most common date-rape drug. Easiest of all to find on UGA’s campus is alcohol itself—especially if you are a 19-year old girl.

Garcia arrived at the house that day with a couple of friends, having bounced around different fraternities’ spring parties—all-day blowouts that attract girls as well as potential new members. According to Garcia, a college-age male approached her quickly after they arrived and asked her to dance.

“‘Let me get you a drink,’ he said. We walk over to the cooler, and a male hands the guy I was with a drink. At the time, red flags didn’t go off,” Garcia says. She had been drinking all day and said she went with it at the time because she was already intoxicated. She said it was an alcoholic punch from a cooler, but that she didn’t know exactly what was in it. “They always say ‘don’t take drinks from strangers,’ but you don’t really notice those transactions, especially when you’re under the influence,” she says. He asked her if she wanted to go upstairs, and Garcia acquiesced.

Kristina Fiske, Garcia’s friend, was with her that night. “There was a guy that was standing next to me, and I asked him, ‘Do you know where they’re going?’ He goes, ‘Oh yeah, they’re going upstairs.’”

Fiske says she must have gotten a positive cue from Garcia to ease her mind about letting her go upstairs alone: “I don’t think I would’ve let some random guy tell me they were going upstairs. I figured she would’ve had to at least nodded to me or something to tell me she was fine. I was worried when she went upstairs. But you also don’t want to be that friend that’s always like, ‘Oh no, you can’t do that, you can’t do this.’ I kind of felt like maybe we’re at the point where we’re big kids and we can make our own decisions now.”

Once upstairs, Garcia and the man were on a futon and started kissing. “We start to make out, and then everything else just kind of goes to black,” she says. “Then it was a sensation of waking up, like a coming-to-consciousness feeling, and I’m laying on my back, and he is on top of me, in the process of having sex with me.”

Disoriented and terrified, Garcia screamed. The man persisted, putting his hand into her mouth to stifle her cries. That’s when the blood started.

Garcia said he got off of her and started screaming, “What the fuck? Is this normal?” Stunned, she said she stood there in shock until he pointed her to a restroom.

“I went to the bathroom and never saw him again,” she says. A girl in the restroom gave her a tampon, and she cleaned herself up as best as she could before finding Fiske downstairs. “When I went outside, I kind of realized everything that was going on and just sat down on the ground and just cried and cried and cried,” Garcia says.

A sign on display at a Take Back the Night rally Friday, Apr. 17.

(Like most media outlets, Flagpole generally does not identify the victims of sexual assault, but Garcia stepped forward to help her healing process, reduce the stigma and bring attention to the issue of sexual assaults among college students.)

At the insistence of an older friend, Garcia sought help days later at the North Georgia Cottage, a local sexual assault center. She received emergency contraception and precautionary drugs for sexually transmitted infections, as well as a Sexual Assault Nurse Examiners exam to collect evidence in case she wanted to press charges.

Devon Sanger, the Cottage’s adult advocate, worked with Garcia in the immediate aftermath. Sanger says a good amount of her clients are UGA students, and alcohol is often involved. “I think that you have to be careful, though, because alcohol is not the cause of sexual assault,” she says. “But obviously, it helps the perpetrator and it inhibits the survivor. The more one drinks, the more likely they can’t think straight or get away, in certain instances.”

A Perfect Storm

“If you're underage and don't have a fake ID, you go to fraternity parties, Greek or not,” Garcia says.

Greek Life Director Claudia Shamp challenges Garcia’s statement, however, saying “that may be your personal experience, but it is not my experience. If underage students want to drink, they’re going to find ways to drink regardless of Greek affiliation.”

Greek affiliation seems to make it easier, though. The Atlantic published a lengthy article in February detailing drunken mishaps at frat houses across the country—not just Animal House-style hijinks, but sexual assaults, falls and other accidents that resulted in serious injuries and deaths—and the lengths to which fraternities go to avoid liability. Closer to home, Georgia Tech suspended the Phi Kappa Tau fraternity earlier this month after a member circulated an email offering advice on "luring rapebait."

Fraternity houses are scattered around Athens, but a cluster of them are located on East Campus in a complex called Greek Park, which is UGA property. The houses there were built in 2009, after the university purchased the fraternities’ former houses on Lumpkin Street.

According to Shamp, the alcohol policy in the houses is determined independently by each organization’s national chapter. Phi Delta Theta, for example, is dry. Consistent among the houses, however, are the policies against serving minors and using common-source alcohol containers like punch bowls or kegs. The guidelines concerning university events where alcoholic beverages are served or provided prohibits the self-service of alcohol, requiring bartenders or wait staff to serve to consumers instead. Despite this rule, organizations do serve from common-source containers—according to Garcia and Fiske, an alcoholic punch was served from coolers on the night of Garcia’s assault.

Williamson says the onus is on the organizations hosting parties to follow the rules. “There’s no doubt in my mind that there are things going on everywhere,” he says. “The reality is that we don’t live in a police state. Our country has rights, every individual has rights, and the police are going to interact with individuals based on the Constitution.”

Fraternities frequently employ security guards to watch over their parties and step in if violence breaks out. UGA police officers are available to work overtime at these events at a rate of $32 per officer, per hour. When they work these shifts, Williamson says they’re bound by the rules and regulations of the department, and that they represent UGA's interests. What these guards do not do, however, is monitor underage alcohol consumption.

UGA Police Chief Jimmy Williamson.

“If I've got 10 people lined up and they’re drinking, who’s underage drinking? You can’t tell. So the police can’t just go up and say, ‘Let me see your ID.’ We have to have probable cause,” Williamson says. “They’re not there checking ID—that’s up to the party. [Fraternities] know they’re not supposed to be serving underage or have common-source containers. If they’re doing something that would make us think, then yes, we would act. But [officers] can’t just walk up to you because you have a beer and say, ‘Let me see your ID.’”

Williamson says that more than 90 percent of the sexual assault cases reported to police involve alcohol consumption, but alcohol consumption is largely unmonitored even at parties where police are present. Instead, he says entities and individuals responsible for preventing assaults deflect the blame from themselves. “What happened to individual responsibility? People complain about the number of laws that are on the books right now. We keep getting more and more laws every year because of people's unwillingness to take responsibility.”

Savannah Downing, co-president of Triota, UGA’s women’s studies honor society, says she is hardly surprised at Williamson’s response. A commonly quoted statistic is that one in four women have been sexually assaulted. “I don’t think that it says UGA police are behind them. I don’t,” Downing says.

Lasting Effects

Garcia hasn’t been in a fraternity house since that night. In the two years since the attack, she has been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder and has attended intense, regular counseling sessions to learn to cope with it.

“I love to go dancing, but I just hated to have any sort of interaction with guys in public,” she says. “Which sounds really stupid, but everything just seemed much more predatory. I didn’t want to go out and meet people, I didn’t want to interact with people, and I especially didn’t want to be interacting with people where alcohol is involved.”

The fight-or-flight reaction to these kinds of social situations subsided with time, and now Garcia is ready to graduate and is focusing on moving forward with her life.

Because the assault happened in a fraternity house owned by the university, Garcia was required to file a police report. She did not press charges, though, and until recently, she had only confided her story to a few close friends, because she didn’t want to be defined by what happened.

“The big thing for me was that my sorority has good relationships with that particular fraternity,” she says. “So I didn’t want that to hurt that relationship, which at this point sounds stupid. I’m definitely more aware now of the fact that this is something that affects one in four women. Period. It’s something that definitely changed my outlook on things, but at the same time, I don’t let it define who I am. No one wants to be ‘The Rape Girl.’”

Timeline:

Sanger says Garcia’s previous desire to remain anonymous is consistent with many survivors with whom she works. “It’s not just the larger culture, but I hear it from friends and family, too, about how specifically surrounding alcohol or being out at bars or parties, that if that person hadn’t have been there, this wouldn’t have happened,” she says. “And really, that is victim-blaming. That is the definition of it. It gives people an illusion of control, like this could’ve been avoided.”

Part of the problem, Sanger says, is a fear of not being believed, “I think so many survivors live in a world where this is not talked about,” she says. “A lot of girls don’t even know that it was sexual assault. When one says, ‘OK, get it over with,’ that’s not really consent.”

More trouble often comes when survivors try to press charges against their aggressors.

Williamson says his job is to prove to the courts that the act was not consensual, which becomes difficult when both parties know each other and have been seen out together. “When a person comes in and they feel like they’ve been taken advantage of—and in almost every way they were probably taken advantage of—but I try to explain to them I can’t lock the guy up for being a jerk,” he says. “There are maybe a lot of jerks out here who probably didn’t treat you with much respect, but when we talk about what happened in the evening, and the way they’re told to us, it’s hard to say sometimes if there was truly a rape.”

Often, a police officer’s role is to find evidence that whatever happened was not consensual. “Typically, with most of the cases reported, we try to backtrack their evening and find video,” Williamson says. “If I find video that the woman is staggering and can barely walk, we’re in a much better situation to say she couldn’t give consent. If they’re seen walking together going somewhere, it’s going to be harder to say that alcohol was a factor and she couldn’t give consent.”

There's a significant gap, though, between what advocates like Sanger define as assault and what actually holds up in court. Because alleged aggressors are considered innocent until proven guilty, the responsibility falls upon victims and their advocates to prove that sexual activity was nonconsensual. Oftentimes, this means aggressors walk free after accusations, due to a lack of evidence.

Downing says this emphasis on proof, rather than women’s words, unfairly alleviates aggressors of responsibility, while placing the blame on victims. “I feel very exhausted when I hear this, because it seems to be the case whether it’s women who have been assaulted, or even in the case of college students in general, it was ways that people need to protect themselves from others. Like other people can’t help it,” she says.

Of the videos Williamson refers to, Downing says, “‘Hey girls, when you go get drunk, make sure you record each other, because you never know when some jerk’s going to take advantage of you.’ That’s what that statement translates to me as. I don’t think that’s acceptable.”

A significant part of Sanger’s job is helping assault survivors understand that what occurred was not their fault, even if they are not able to move forward with a case. “We depend on the legal system to tell us whether or not something happened, so I think when a victim hears something is unfounded, or it’s not going to be prosecuted, that undermines the validity of their story,” Sanger says. “A lot of my role is saying that just because that couldn’t go forward doesn’t mean a sexual assault didn’t occur.”

The Interfraternity Council, the governing body of men’s fraternities at UGA, requires new members to attend an educational session each fall where Williamson speaks about consent, among other topics like alcohol and drug use.

Williamson says parental engagement on these tough topics is one way to help solve the problem, which can’t be solved in a single lecture: “If one lecture could fix it all, we’d all have a lecture and be done with it,” he says.

Sanger agrees, saying that a single educational session isn’t enough to affect a cultural shift at the university. “If you just hear it once, and you’re raised in a society where rape is normalized, hearing that message once may be helpful, and may make some people think twice, but it can’t undermine an entire lifetime of socialization,” she says.

Sexual assault occurs everywhere, but at UGA, underage students are given frequent—and nearly unlimited—access to free alcohol on a weekly basis with little supervision or consequences. With such minimal education on rape culture and consent, it’s no wonder assaults like Garcia’s occur.

“At some level, who is to be held accountable for this?" Sanger asks. "I think we all are.”

comments