Rock Climbing 101: How the Sport Has Grown from Its 'Dirtbag' Roots

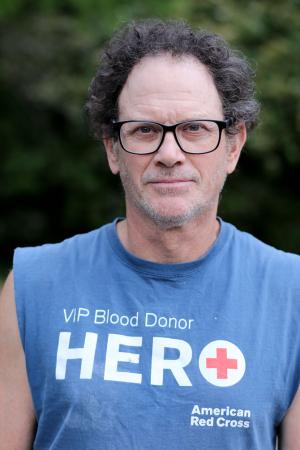

Photo Credit: Joshua L. Jones

Adrian Prelipceanu (center) instructs a young climber at his gym, Active Climbing.

The face of Athens climbing, for many, is a small Eastern European man. Active Climbing owner Adrian Prelipceanu grew up in the mountains of Romania and began climbing at 18.

“I’ve done a lot of crazy stuff in my life,” Prelipceanu says. “And climbing was one of them.”

At first, he climbed long routes without gear. This dangerous practice is called free soloing, and Prelipceanu is now vocally against it. “I did not know, actually, that I was climbing,” he says. “But then we found out that there are, like, ropes and harnesses.”

When Prelipceanu began in 1992, equipment was just becoming widely available. “But then it just started exploding like anything else—so many options for shoes, so many ropes, equipment, you name it,” he says. “And I think that all that together was a big change to how everybody looked at climbing.”

But even after he donned a harness, many were taken aback by Prelipceanu’s new hobby. “When I started, it was considered a dangerous sport,” he says, and when he mentioned climbing to new acquaintances, they put him in “a crazy bucket—‘OK, you are one of those crazy people.’”

Media coverage didn’t help climbing’s image, he says. “Every time they presented something, it wasn’t that somebody just had the first ascent on that wall or whatever,” he says. “It was just like, ‘Hey, there was an avalanche. Yeah, it killed like 10 people, you know: it was a climber that fell [off] a cliff.’”

Popular perception of climbing is different now, with blogs, podcasts and Instagram accounts dedicated to the sport and its obsessives. Professional climbers such as Sasha DiGiulian and Tommy Caldwell are sponsored by big brands like Red Bull and Patagonia. Rock & Ice, Climbing Magazine and Dead Point Magazine cover every aspect of the sport. Climbing is finally mainstream.

Prelipceanu won competitions, established new routes and even ice-climbed. He coached climbers and managed development projects. He also mountaineered, summiting peaks in Turkey, Argentina and more. Finally, he moved to Atlanta, helping to open Suwanee’s Adrenaline Climbing gym in 2003. In 2009, he opened Active after surveying climbers at the Ramsey Student Center during a community competition. He knew there was a seedling climbing scene outside UGA, and he decided to create a space for its growth.

From the survey, Prelipceanu knew that Athens wanted a bouldering gym. “That was one of the things everybody had mentioned,” he says. Bouldering has recently become popular as a more accessible and less expensive alternative to sport and traditional (“trad”) climbing.

A Rock-Climbing Glossary

Rock climbing has its own language. Here are a few terms to know.

Trad (“traditional”) climbing: The climber places protective gear on the way up a rock face and then clips her rope into that.

Sport climbing: The climber clips into bolts drilled into the rock. Sport routes tend to be shorter than trad routes.

Bouldering: The youngest climbing discipline. Boulderers climb at low heights and don’t use ropes, harnesses or other gear; but if they fall, they fall onto the thick foam of crash pads placed on the ground.

First ascent: When someone climbs a route before anyone else.

Prelipceanu looked at several buildings before choosing a dilapidated poultry freezer on Barber Street. Active Climbing opened its doors in April 2009, after Prelipceanu restored the building. It later won the Athens-Clarke Heritage Foundation’s Outstanding Rehabilitation award. Most recently, Prelipceanu built an addition onto the gym and moved his family in.

Active’s bouldering gym features a variety of wooden walls built at funky angles and covered in plastic holds to mimic the shape of rock. Prelipceanu made its enormous crash pads himself under his label Big Ass Pads. Two sport routes traverse the roof, and aspiring acrobats can practice aerial skills and trapeze. Across the lobby is a smaller gym, which is ideal for top-roping (climbing with a rope running between the climber’s harness and the top of the route). This room is popular for birthday parties, and kids can climb on the playscape and on the painted giant.

Regulars include students, professors and every type of townie. Prelipceanu coaches the Georgia Spiders, Active’s competitive youth climbing team, which has seen kids go all the way to nationals.

Community is important to Prelipceanu, who decided to put benches in his gym after seeing climbers congregate on some in another. “It was a small gym, but everybody loved that one just for that reason,” he says. “‘Cause everybody knew each other. I want to have that feeling, where people know each other.”

Active is larger than UGA’s climbing facilities but tiny compared to gyms like the enormous Stone Summit in Atlanta. Still, Prelipceanu says, it is just right for this city. “Everything in Athens is tiny,” he says. “You’re not gonna find anything humongous, and I think it fits just perfectly.”

The Beginners

Before Active entered the scene, Ramsey was the only player.

The UGA climbing wall underwent a design overhaul in 2010, but its first iteration opened with the Ramsey Student Center in 1995. Since then, it’s been a resource for university-affiliated serious climbers and vertical newbies alike.

“I would say that if you look at climbing as a funnel, we’re the widest part of the funnel,” says Kellie Gerbers, assistant director of UGA Outdoor Recreation. “We are the place where a lot of people go to first discover climbing, learn basic climbing technique and fall in love with climbing.” The wall hosts advanced climbers, she says, but a typical progression at Ramsey is for someone to try the sport, get hooked and then seek a bigger facility.

Nate Herest practices with the Georgia Spiders youth climbing team.

Ramsey offers indoor top-roping and an outdoor bouldering area. Aspiring top-ropers must attend a safety clinic, but anyone can boulder if the weather is nice.

“We are kind of that introduction to climbing, because you walk by this 40-foot wall every day,” student wall manager Evan Thorsen says. “Eventually—hopefully—it’s gonna pique their interest, which is why we’re here.”

Whereas some climbers use gyms to improve at outdoor climbing, many Ramseyans stay inside. Some have climbed in Moab and other hotspots, Thorsen says, but it’s a mix. “I would say your average climber, if you were just gonna randomly point at one, probably hasn’t been outside yet,” he says. It’s often a question of new climbers finding someone to take them out. Fortunately for them, UGA offers weekend trips in North Georgia to introduce new climbers to real rock.

Although Ramsey’s climbing area is small, its proprietors work hard to promote the sport. When Active hosted the Collegiate Climbing Series competition, Ramsey climbers helped with logistics. “I don’t know that we’ll ever get to the point where we’re hosting those styles of competitions,” Gerbers says, “but we’re certainly happy to team up with other schools or other gyms that are.”

Each November, Ramsey hosts the Boulder Bash community comp to benefit the Southeastern Climbing Coalition. A free screening of the climbing documentary Valley Uprising drew a crowd into the bouldering courtyard in April, and events such as Ladies’ Night and Try Climb allow students to top-rope without committing to a clinic. “We’re trying to be a little bit more universally accessible,” Gerbers says, “so that climbing is not just for climbers, but it’s for everyone.”

The Badass

Jeep Gaskin is something of a Southeastern legend. He climbed way before it was cool, when crash pads were carpet squares and climbing shoes more closely resembled Chuck Taylors than the tiny elf slippers worn today. He learned the ropes after bicycling across the country at age 18.

“I think of it now, and I just go, ‘What the hell were my parents thinking?’” he says. “But I saw the Tetons and was in love immediately.”

Gaskin returned to Wyoming in 1973 for a few climbing courses, including one from the now-legendary Jim Donini. He had found a new obsession and a new community.

The climbers of yore embody the “dirtbag” image now coveted by a generation raised on plastic. Valley Uprising is the story of greasy men—and a woman—for whom climbing was life. That meant sacrificing basics like real food, housing and hygiene to climb full-time.

A newer, more aesthetic version of this lifestyle now sparkles through Instagram filters, but the original dirtbags were truly countercultural, and there weren’t many. “It was really a small world, is really the point I’m trying to make—that you would run into someone like Donini working at a guide service in Wyoming,” Gaskin says. “But yeah, I moved back to North Carolina, and it was a case of a whole lot of things to climb and not many climbers.”

That’s why Gaskin’s name is on so many routes in North Carolina. Sport climbing didn’t really exist in the U.S. back then, so all of Gaskin’s first ascents were trad. “That’s all that there was when I started,” he says. “There wasn’t the differentiation. Bouldering was just to improve a workout to get better. It didn’t really exist as a sport in and of itself.”

Although trad was once the only climbing option, it has waned in popularity relative to sport. One barrier is the expense of equipment, but another deterrent is the responsibility trad climbers must take for their own safety. When you clip your lifeline into a piece of gear, you’d better have placed it well.

“That keeps a lot of kids, I think, now from doing trad,” Gaskin says. “They are intrigued by going different places and doing larger climbs, but they’re uncomfortable setting anchors, building anchors. Because they and their partners’ lives depend on the quality of the anchor that they built.”

For Gaskin, though, fear is nothing to shy away from. “It’s wonderful,” he says. “It’s the reason you come back. You know, there’s this gymnastic quality, and it’s nice to feel powerful, but when your strength is put to the test—that’s when you decide if you can get up or not. And that’s when fear enters. And it’s inescapable.”

Gaskin worked as a guide for a time, even leading an ice-climbing expedition in Alaska. “That was the hardest $1,000 I think I ever made,” he says.

He moved to Athens the next year, then raised three children, all climbers. “We’ve had Gaskin family picnics that involved climbing some of the biggest cliffs in the Southeast,” he says. “It’s been really good.”

At 62, Gaskin climbs at Active during the week and still gets out a few times a month, but parenthood long since ended his serious climbing days. “I don’t regret it, really,” he says. “I think I would regret it more if I hadn’t pushed to the point of failure.”

Some trad purists insist that bolting rock faces, or even using climbing chalk, is unethical. Gaskin does not agree. “When the climbing gets hard, every single climber worth anything at all adapts their tactics,” he says. “The only real rule in climbing is to come back to climb another day. That’s all that there is. So when the chips are down, you’re gonna bolt.”

From an ethical standpoint, the environmental effects of climbing, however, are undeniable. Improper disposal of human waste is a huge issue, Gaskin says, but not the only one. “Where we put our crash pads, the flowers, the vegetation, things are just beat flat,” he says. “And when it rains, it turns to mud, and that’s not natural. We have changed the ecology there, and it’s a shame.”

The ever-increasing popularity of gym climbing means more climbers going outside, which means a greater environmental impact. “We have to be stewards,” Gaskin says. Still, he says, the altered face of climbing isn’t ugly.

“The gym climbing has, in my estimation, been really good. It’s good to see,” he says. “When I started climbing, it was largely a bohemian group that climbed, and now it’s not that way. It’s a lot more young people who I hope continue to climb, but who will go on to do other things besides just dirtbag. But we dirtbagged.”

The Young Gun

One ex-Athenian is currently living the dirtbag dream. John Wesely graduated from UGA in 2011, stuck around until 2013, then moved to Kentucky to live in a tent. Slade, KY’s Red River Gorge is a premier destination for sport and trad climbers.

“One of the best things about living in the Red River Gorge is that I get to meet people from all over the world,” Wesely says. “The climbing is truly world class here, and it is not uncommon for English to not be the most common language overheard at the crag during peak season.”

Many climbers visit the Red for short-term adventures, but a community of tent-dwelling rock fiends camps full-time behind Miguel’s Pizza, a bastion of American climbing in its own right. Wesely was once a campground denizen but now has a home of his own. “I currently live in an apartment attached to a beer store in the Gorge, which makes me one of the few not-homeless people I know,” he says.

Even with walls and a floor, living in Slade is a special experience. “The core community here is really small and tight-knit. That, combined with the general unity of purpose, makes it a pretty incredible place to live,” Wesely says. “The vast majority of the people who live here dirtbag it in tents or vans. The fact that they are willing to do that to live here says more about how special this place is than I ever could.”

Wesely started climbing at 15. His first crash pad was a homemade affair fashioned from deck chair covers. “I was instantly psyched,” he says. “Bumming rides, paying for climbing gym dues with change, doing pull-ups on door frames, and generally being a little climbing junkie.”

He started college before Active opened. “I will forever be thankful to the Ramsey wall introducing me to almost all of my best friends,” he says. “That being said, Active is a fabulous facility with a great community, and I was thrilled with the gains I made once I switched over.”

Wesely climbs for the challenge. “The rock doesn't change,” he says. “If you aren't good enough, you can come back next year. It is also a consistently humbling experience. The better I get, the more I realize how much I still have to learn.”

In 10 years of climbing, Wesely has already witnessed changes in the sport. Climbing culture has changed along with culture in general, he says, and “the social media explosion has had a tremendous impact.”

In 2005, he says, few climbing media and scarce guidebook options existed. “Now you can find a video of virtually any climbing route on YouTube, and even satellite areas have guidebooks brimming with color photos and detailed route maps,” he says. “Almost all of this new media is user generated, which is fantastic, but it does seem to have diminished the adventure.”

And Wesely’s life is all adventure. He spent last winter bouldering in California. “Amongst other things, I learned how to find firewood in the desert from a guy who lives in a teepee, and I built a meat smoker,” he says. “The climbing was great, but I will never forget eating smoked turkey breast with my friends around a roaring campfire. That has to be the easiest way to feel like a king.”

Living at the Red means sometimes climbing with the pros. Since professional climbers spend most of their time on rock, Wesely says, it’s somewhat common to run into them at the crag. “Yesterday, I had the pleasure of sharing a cliff with one of the top five sport climbers of all time,” he says. “This sort of thing happens fairly often but is the equivalent of a kid playing rec ball getting to play a pick-up game with Michael Jordan.”

For now, Wesely manages the Red River Rockhouse, a climber-owned farm-to-table restaurant, and takes photographs on the side. The gig allows him ample climbing time. What lies ahead? That’s an unbolted line. “Right now, I have no idea what the future holds, and I am totally OK with that,” he says. “Whatever I do in the future, I want climbing to be a part of it.”

comments