All My Trials, Pt. 1

Pub Notes

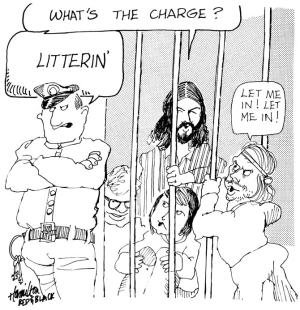

How The Red and Black saw it on May 4, 1972.

This week’s symposium at the law school (see last week’s Pub Notes) on famous Athens-area cases brought to my mind the case I was involved in that didn’t make the cut for the legal gathering. The trial of “The Athens 8” came at the end of a period of campus activism that involved sit-ins and riots and culminated at Kent State University with the killing of four students by National Guardsmen.

On campus here, student activism had taken a more political path (except for the attempt to burn the ROTC building), with the eventual election of a liberal-progressive student government, headed ultimately by an unashamedly gay leader. Meanwhile, the university also had a new, young president who was installed to oversee an influx of money appropriated by the legislature for the purpose of rapidly expanding and upgrading the university, which already had been through a building boom that included the high-rise dormitories along Baxter Street. In the attempt to assure that the high-rises did not turn into isolated student ghettoes, the university had instituted programs to extend academics and trained student counselors into the dorms, to try to blur the lines of separation between learning and living. The program was highly successful and much studied by other schools across the country—and by a certain South Georgia lawyer, who discovered that it included a co-ed dorm, where men and women lived on alternate floors, and his daughter was one of those women. He blew the whistle, and the legislature expressed its displeasure. The university began to dismantle the dormitory programs, causing the students who were part of them—many of whom were also involved with the student government—to resist the end of what they saw as a vital, effective outreach. Rebuffed by the university administration, the students—dorm counselors and student government representatives—sought an audience with the president, and were ignored. Thus ensued the last of the college sit-ins, long after the tactic had played out across the country, after the university had spent half a decade formulating plans on what to do if it happened here.

Thirty-three students entered the office of the president and declared their intention of remaining in his waiting room peacefully until the president would meet with them. Having heard about the effort, I walked over from my campus office and joined them, to show faculty support for what they were doing. Shortly after I arrived, so did the campus police. We were all arrested, handcuffed, charged with criminal trespass—a misdemeanor punishable by up to $1,000 fine and a year in jail—and taken to a cell upstairs in the court house. My office keys were confiscated as dangerous weapons, and I never did get them back.

Shortly, we posted bond, and then began a long period of legal maneuvering and pressure from the university and the judge that convinced most of the students to accept a light fine and probation rather than face certain jail time if they fought the charges. The kids got a quick and invaluable lesson on just how costly activism could be when the university teamed up with the court to threaten interrupting their college careers with jail time, and thereby their future lives. Most of them, tearfully, regretfully, took the deal and paid their fines.

When the weeping and wailing and gnashing of teeth were over, eight of us, for various reasons, refused the deal and began trying to figure out how to fight the charges that had the potential of disrupting our own lives and making student government irrelevant.

Next time: the trial.

Hear “Live with Gwen and Pete” Thursdays at noon on WXAG AM-1470.

More by Pete McCommons

-

Voting Absentee: Necessary But Not Easy

Pub Notes

-

Be Ready When National TV Comes Calling

Pub Notes

-

comments